Wilderness Medicine Lessons to Help Your Business Thrive

- By Kevin Foley

- •

- 30 Jun, 2019

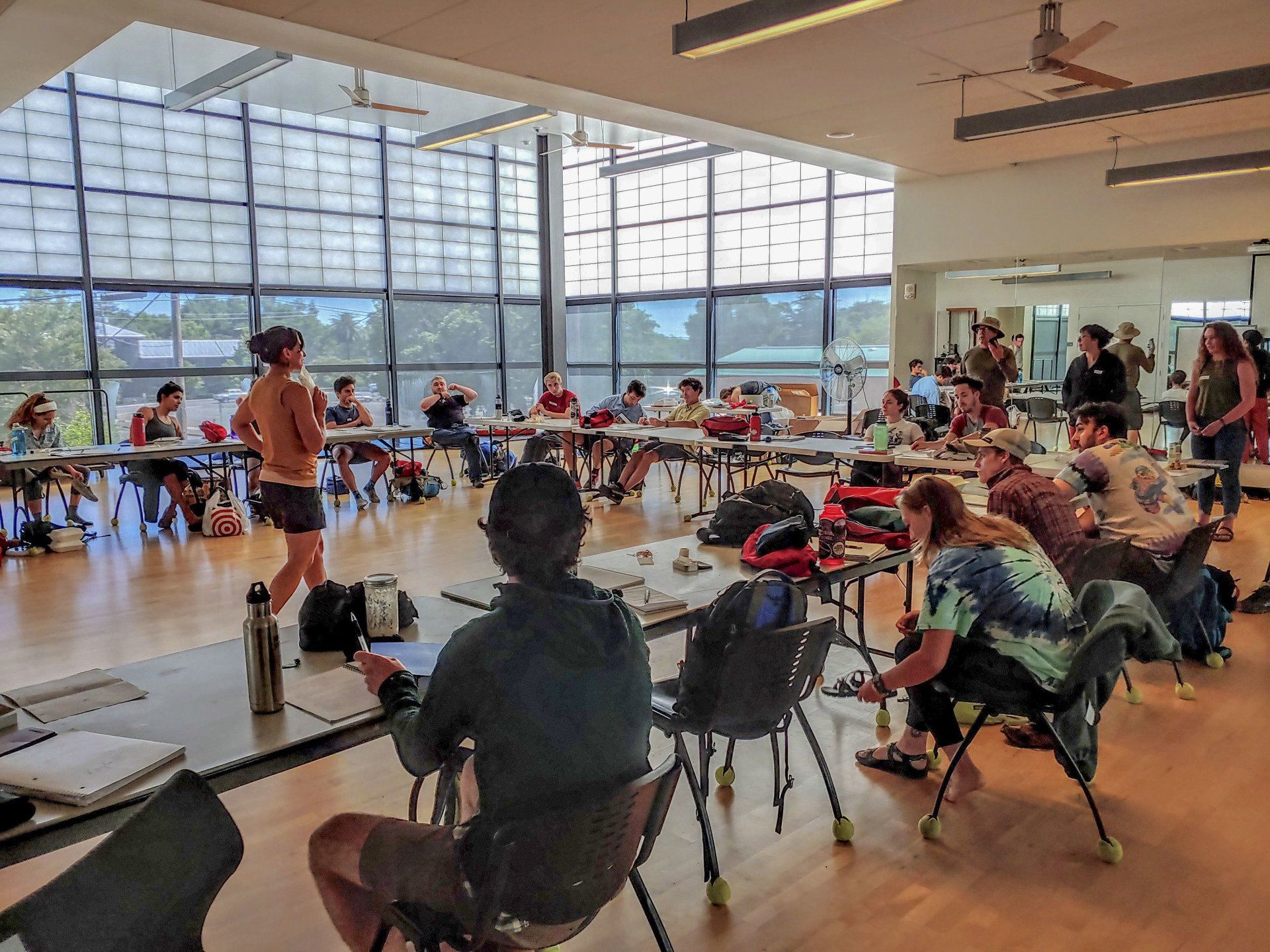

Earlier this month I completed an 80-hour wilderness medicine training course. It was filled with dozens of lectures, quarts of fake blood and no shortage of hands-on practice - both as a rescuer and a victim. There were approximately 22 students and two seasoned instructors. My classmates came from many different backgrounds, and included backcountry trip leaders and guides, search and rescue volunteers, nursing students, park rangers, and even one sustainability manager & consultant (guess who that was?). The 80 hour course was split evenly between in-class lecture and hands-on practice.

What is Wilderness Medicine?

According to the 18th Edition Wilderness Medicine Handbook, Wilderness Medicine is practiced in the context of delayed access to care, in challenging environments, often with the need to improvise gear, with limited communication and independent decision-making on the need for and urgency of evacuation.

Why I Chose to Get Certified

As intense or even "scary" as this situation was, I was also in the “front country,” or an urban setting, which meant that “definitive care,” or modern medical facilities (hospitals), were only minutes away. However, in the “wilderness,” or “backcountry,” (or any place that is hours or days away from definitive care), the rules can change. Time spent with the patient is greater, and time from the onset of illness/injury to definitive care may be much longer. For these and potentially other reasons, a person's injury may merit a different treatment approach than it would in an urban context to ensure the best possible outcome.

While I am most often in the front country, I enjoy spending as much time as I can in the backcountry. Given this fact, the concept of wilderness medicine was not new to me. In fact, I had taken a two-day Wilderness First Aid course four years ago. The Wilderness First Aid course was 18 hours long and administered by the National Outdoor Leadership School, or NOLS. It was an informative class and I learned a great deal.

However, despite my 18 hours of training, I couldn’t kick the feeling that I was only mildly prepared for the situations I might encounter. I knew I had only scratched the surface of the broad field of wilderness medicine. These feelings re-surfaced when my family member was injured and I was called upon to manage her initial treatment and get her to definitive care.

It was after this incident that I made a decision to commit to the 80-hour Wilderness First Responder Course. The Wilderness First Aid course had breadth, but the Wilderness First Responder course had breadth with depth. I knew that if I ever wanted to take my knowledge to the next level, this 80-hour First Responder course was my answer.

Lessons Learned

While the instructors sent us out with confidence and a feeling of empowerment upon our graduation from the course (and although there’s so much more to learn), they emphasized one point over and over. They said, “The best tool in wilderness medicine is not something you keep in your emergency kit, but the organ between your ears.” Using your brain can help you avoid needing wilderness medicine at all. The best medicine is in fact preventing injury and illness in the first place.

When you’re in the wilderness you’ll never have all the supplies, tools, or personnel needed to truly treat a severe injury. One must always be transported to “definitive care” (aka a hospital). If the injury is bad enough and/or the location is remote enough, this must often be done via a rapid evacuation, typically in a helicopter. The bottom line is that getting injured in a remote backcountry setting can have serious consequences. Whenever possible, you should prevent injuries in the first place.

A passage from the Wilderness Medicine Handbook illustrates this idea nicely. “Experienced wilderness leaders know it’s much easier to stay warm than to warm a hypothermic person in the backcountry. Whether it’s hypothermia or hygiene, prevention is an important theme in wilderness medicine.”

Ben Franklin once said: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” His advice carries a simple but powerful message, and, if taken to heart, could someday save your life. Prevention is king.

However, Franklin’s timeless wisdom isn’t exclusive to the world of wilderness medicine.

Lessons in Sustainability

Smart businesses don’t wait for their sustainability program to serve as a “rescue device.” They use it as a tool for prevention. Begin capturing the benefits of sustainability right now, on your own terms, and reap the rewards that come with it. Do not wait until you’ve been slapped with a hefty fine, forced to comply, or even worse, forced to shut-down your business entirely. These unwanted outcomes are easily avoidable with a bit of preventative planning.

Check Your Ego

Ryan Holiday said in his book Ego is the Enemy, “Pride blunts the very instruments we need to succeed: our mind, our ability to learn, to adapt, to be flexible, to build relationships, all of this is dulled by pride.”

A big part of prevention is having the self-awareness to leave your ego out of the equation. To allow your ego a spot at the decision-making table is to leave your thinking brain behind.

Conclusion

We hope you enjoyed this article and decide to take action in your own sphere of influence, whether that be sustainability, wilderness medicine, or any other endeavor that is worth pursuing.

If you liked what you read and want to learn more, please sign up for our email list and share it with others, or follow us on instagram to get notified of our newest articles and other updates.

As an adult watching the new remake nearly 25 years later, I was equally captivated.

As most who have seen the original Lion King can attest, it is chock full of invaluable life lessons. It effectively illustrates examples of leadership, courage, forgiveness, justice, faith and purpose, to name just a few. Like the original film from 1994, the remake did an excellent job of capturing and illustrating all of these lessons. This time around, one lesson that really stuck out to me, which I hadn’t caught in years past, was that of sustainability.

As a 31 year old who has dedicated my entire professional career to sustainability, I am constantly on the lookout for little gems of sustainability wisdom. Whether or not I intend to, I view just about everything through that lens…including Disney remakes of old classics. In this new version of The Lion King, I found one of these gems that I am always looking for. As a quick aside, if you have not seen the Lion King (original or remake), some of what lies ahead could spoil some of the movie for you. If you fall into that category, proceed with caution.

While in the movie theater, I didn’t have a pen and paper with me, and the lights weren’t on...so I was unable to take any notes or write down any quotes related to the gems of sustainability wisdom I witnessed. Since I was still thinking about the movie weeks later, I decided to go back and watch the original movie at home, so that I could take notes, pause and rewind as needed, and see if my observations about this classic movie truly held their own.

If you have not read Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, we suggest you go back and read them. They will give you a solid understanding of what sustainability is and why it is important for organizations like yours.